This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

A legacy in music: PSO Blogs

[Original at the Pittsburgh Symphony Blogs]

This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

This weekend marked the end of another season for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But it marked the end of something more. Three esteemed musicians were retiring from the PSO, Charlotta Klein Ross (cello), Ronald Cantelm (Bass), and James Gorton (Oboe). My wife has a particular connection with one, having performed alongside one. And the program reflected one type of legacy, with Gorton; his wife, Gretchen Van Hoesen; and daughter, Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, being the soloists for Goossens' Concert Piece for Oboe/English Horn, Two Harps and Orchestra as the close for a career and a season.

Certainly one way to have a legacy is through your sons and daughters. Another is through enabling a future through gifts that allow others to flourish. But what are the things that one does to create a legacy? One is through the development of raw talent, the sort of thing that we explicitly recognize when we attend a PSO concert. But while it is memorable, it is fleeting. What does it take to create something that endures?

I can think of two ways. First is to create something based on an idea, then invite others to build upon it. It is creative not only in the creation itself, but the idea and concept that can be built on. One recent set of projects surrounds the MusOpen project, which raises funds for the development of public domain scores (including computer source that makes the score) and recordings. The first is having its first fruits, with the Open Goldberg Variations and recordings of the Prague Symphony Orchestra in support of that project. The second is to teach and train the next generation.

Always there are risks. For the first, the question that always gets stated is why do things in a different way. There are certainly scanned copies of Bach's Goldberg variations and other scores, and many editions that have been put together by dedicated scholars. But now the promise is that the music (both the description as well as the performance) can be used as a starting point in other creative works, which requires both the right to do so as well as source material that can be modified. And for the second, the question is if it makes a difference, especially when the deepest knowledge can only be passed in one-on-one interaction.

My wife and I are both at stages in our careers where we make commitments to the future. And part of that is the fact that much of what we leave behind is not going to be what we ourselves create, but in ideas and organizations passed on to students and colleagues whom we have the pleasure of working, contending, and building with, and new ideas that are developed and grown into institutional capabilities and memories.

I was listening to the stories of the musicians retiring with this season, and I was thinking about the legacies they leave behind, which was more than tales of inspired musicianship, although that was there. It was in the creation of memories, and investment in others to guide them to their futures, musical or otherwise. And in that is something worthy of the name legacy.

Saturday, June 02, 2012

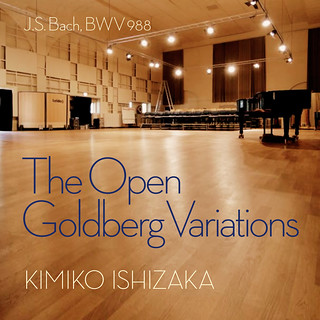

A free, public domain recording of the Goldberg Variations performed by Kimiko Ishizaka

Last Monday was marked on my calendar as the release of The Open Goldberg Variations performed by Kimiko Ishizaka. Why was that special? It was the release of a crowd-funded professionally performed, recorded, and produced recording and score of Bach's Goldberg Variations into the public domain. It is a throwback to the old system of patronage for individuals supporting artists and their works.

Arguably, the enduring contribution of this is the release into the public domain of both the score as well as the MuseScore source file. As programmers know, the release of the source file in an open format with an open source implementation means that this will be available for re-formatting, re-publication, and combining with other similarly licensed works forever. It also means that the score has been examined, not only by those who were directly funded by the project, but by anyone who had the inclination and interest to participate in the project over the past year. The process was open for examination not only for correctness, but also feedback and ideas. No small matter in piece that was meant for a double manual (keyboards) of a harpsichord instead of the single keyboard of a piano. While the notes may be by J. S. Bach, how it is presented and arranged so a pianist can play it when the physical layout of the instrument is different then intended matters. The challenges of this have lead to improvements on the open source MuseScore composition and notation program (and I for one am waiting for the release that includes these improvements to come out). Aaron Copland (and others) have stated that music is a collaboration between composer, performer and audience. In many cases, the third is often diminished, reduced to paying for tickets, recordings, and donations. But here, the fact that the audience could contribute was taken seriously.

I'm already familiar with the piece from the 1955 Glenn Gould recording. And since the release of The Open Goldberg Variations I have had this playing in the background continuously while working. Which, come to think of it, is not much different than the original purpose of the piece, to provide something to be played by Johann Goldberg to play for the Russian Count Kaiserling to cheer him up during his insomnia. And last night when everyone else in the household went to bed, I stayed up to listen to this with a copy of the public domain score (from MuseScore.com) in front of me.

Looking at the score, one obvious note is the utter absence of dynamics and tempo markings. Which leaves considerable room for interpretation. The range of the 30 variations (plus the base Aria and final Area da Capoe è Fine) allows the pianist to show her range, and Ishizaka provides something to hear. As expected, she does not make the same choices as Gould. And she does not seem to be in as much of a hurry as Gould was. And the recording became a delight as she worked her way through the variation, each with its own feel, even with each repeat.

Here in Pittsburgh, I've had the please of being a part of an experiment by the Pittsburgh Symphony to involve a part of the audience as part of its blog. Because for the audience to take its place in the three aspects of composer/performer/audience there should be more response than only our monetary support of institutions, but to contribute to criticism and direction of the art. And this project pushed that in a way not common today.

Is this model sustainable? Since it was funded through Kickstarter, the professionals involved did indeed get paid. Looking at Kimiko Ishizaka's website, she seems to have a nice international concert schedule with many recent and future bookings that are easily attributable to her participation in this project and the Well Tempered Clavier (which is a potential following project). Similar to programmers making a name and reputation for themselves by contributing to open source projects, Ishizaka seems to be taking advantage of the additional exposure coming from her participation. And similarly to open source, the observation is that professional quality work on well run and managed projects leads to high quality products and opens leads on future work.

If you have any interest in listening to classical music, I highly recommend downloading the recording (MP3 and FLAC available at Soundcloud below). If you want to follow along with the score, or if you are thinking of actually playing this yourself, get the score from MuseScore.com.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)